|

Courage to Continue by Cody Eubanks Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow - Cody Eubanks and Joyce Payne approaching 100 miles What will you do when there is no finish line or predetermined measure of completion? When it hurts so badly but there's still time on the clock? The question beckons: WILL you continue? Backyard style ultras are a whole other animal and my favorite style of racing looped courses. Aside from the social aspect, backyard style ultras generate a sense of equality and an illusion of hope that one can continue on much longer with no definitive end. It seems easy, and in many ways, it is, until it isn’t. How did I get here?

Queeny Backyard Ultra is put on by the Terrain Trail Runners in St. Louis, MO close to my hometown Jefferson City, MO a short 2-hour drive. The course is a combination of chat gravel, pavement and short sections of dirt trails with plenty of hills to keep things interesting. I had gotten my start in ultra-running within this community, and I couldn’t think of a better way to start back again! As I wheeled my cooler up to the staging area, we were greeted by the cold, thirty miles per hour wind gust and the rain came in sideways. The tent city was under siege. To everyone's surprise, there was even a registration on race day! A runner had signed up to run the morning of the race, needless to say ultra-runners are incorrigible. The only way to stay warm was to run and at noon, we ran! After four hours of steady downpour, the sun showed its glorious face before fading into a clear, cold night under the waning moon. I stopped to watch the light from my headlamp slither onwards like a snake. The daffodils slumped as the frost set in and the pack of runners dwindled in number and enthusiasm. As conversations ceased and playlists recycled, I looked forward to the morning, daybreak will eventually come. Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow Perhaps it was the excitement of the potential warmth from the sunrise, or the pursuit of 100 miles, but my splits began to get faster. I had been running 50 minutes per 4.2-mile loop for much of the night, with a few catnaps here and there, but the day brought 48s and then consistent 47s. Over the course of twenty-four hours of running the Queeny Backyard Ultra loop I had perfected the course down to a science. In backyard style ultra-lingo, it’s called the “robot mode” and I knew when to walk and when to run. James Pratt, my one-man crew had been with me all night and had taken over my brain duties, as I continued on, visits from family and friends with food deliveries uplifted my spirit. In my head I knew to win a race with no end, I had to muster the courage deep within me to continue, and just keep moving forward until I would be the last person standing. Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow - Cody Eubanks at daybreak After 24 yards the pack of five runners thinned out to only three runners when Kevin Rapp and Joyce Payne decided to drop out of the race. Joyce had led a record shattering effort for the ladies with a 24 yard performance! The remaining three Jason Kesterson, myself and Chris Silva ran a solid 27 yards after which Chris refused to continue and Jason walked back after leaving on the 28th and final lap while I continued on the loop. As I approached the finish line, I was greeted by cheers from the volunteers, my family, friends and my crew James, followed by a finish line hug from the race director. This finish line feeling is not something I will soon forget, but I know I will be back in 2024 for that Silver Ticket for BIG’s! Photo Credit: Janzow Photography

Inaugural Thunder Chicken 100K Stage Races – Lisa Kennedy Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow - Lisa Kennedy amidst Stage 2 The summer of 2021, I found myself on a women’s only group run, led by Shalini Bhajjan, founder of Terrain Trail Runners (TTR) and race director of several St. Louis-area trail ultras. I recall my conversation with Shalini clearly from that day, as she poured on about her excitement for a race, she was putting together for the Fall of 2022 that would be the area’s first 3-day stage race, starting and ending at Camp Wyman. Camp Wyman is tucked away in the rolling hills of Eureka, MO, established in 1898 and connects to some of St. Louis County’s toughest and most beautiful trail systems. This made for a perfect hosting location for this 3-day stage race along with presenting an opportunity to give back to the Wyman Center for their continued work with young adults. Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow - Start of Stage 1 Fast forward a year and half later I find myself at the starting line of the inaugural Thunder Chicken 100K Stage Races in Eureka, MO! Three days of racing encompassing up to a 100K in distance and over 10,000ft of elevation gain, touring three very different trail systems starting with Rockwoods Range Conservation Area, Greensfelder County Park and Rockwoods Reservation Conservation Area. To top all of this, Thunder Chicken 100K Stage Races is the first foot trail race of its kind to take place on some of these trail systems connecting all three parks over the course of three days! Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow - On Course Stage 2 Stage 1 started on some woodland trails in Camp Wyman that connected to Greensfelder County Park as we made our way to Rockwoods Range on some glorious single-track trails. Once in Rockwoods Range runners were presented with some steep climbs and gnarly terrain, running through this section of the course required all of my concentration as I was easily distracted by the changing colors of the oaks and maples that set the landscape ablaze! At the turnaround aid station, I was greeted by the familiar and friendly faces of enthusiastic TTR volunteers to give me just the morale boost I needed to make it back up the steep climb I had just descended. Runners then made their way back to Camp Wyman to close out day one at 21 miles with approximately 3,350ft of total elevation gain. I finished feeling tired and achy and asking myself, “how am I going to get up and do this again tomorrow, knowing that day two is 6 miles longer and steeper?”  Stage 2 kicked off with a beautiful sunrise and offered a grand tour of Camp Wyman’s grounds, leading runners through the trails on the other side of camp from where we had started the first day. This section included some big climbs and descents, taking runners past some old rustic cabins, around to a small frog pond and through an amphitheater before spitting us back onto trails connecting to Greensfelder County Park. After cruising along on some flow trails through Greensfelder we then made our way out to Rockwoods Reservation on Greenrock Trail. This segment of the course was steep, single-track trails with lots of technical sections and rocks covered in green moss to keep you present, thence the name Greenrock Trail. With a quick stop at the aid station, I was on my way to tackle a series of very steep and rugged trails within the Rockwoods Reservation Conservation Area. As I made my way back to the aid station once more the fatigue from day one and the steep, technical climbs from day two had started to wear down on my legs. I topped off my water and prepared myself for the next 10 miles of rugged terrain. I cruised back to Camp Wyman, having already hit 26 miles on my gps watch, I was sure it was all downhill to the finish. And then I turned a corner and bam, one last long climb. I cursed Shalini under my breath and power hiked my way up. At a little over 27 miles and 4,650ft of elevation gain later, my legs were now trashed. I went home to soak in an ice bath and hoped for better sleep. Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow - On Course Stage 3 I woke up on day three eager to get back to Camp Wyman and join my fellow runners so we could all finish what we had started. Stage 3 was the shortest stage at 15 miles with an elevation gain of around 2100ft, but Mother Nature threw some rain at us adding to the challenge. I made my way to the starting line and could feel my hamstrings tighten up, but I was ready to run. What made Stage 3 interesting was the course layout that included some fast flow trails along with few short but steep road sections as well as the challenging and rugged Mustang Trail in Greensfelder County Park. We sloshed and slid down the steep hills and cruised on the more rolling sections of the course.  Coming into the finish I was overcome with emotions! I felt in awe of what the human body can endure. I also felt overwhelming gratitude for this community of people that make these events possible and provide unending encouragement along the way, including race directors like Shalini that dream up these crazy adventures for us to test our limits. Thunder Chicken 100K Stage Races is the latest of Terrain Trail Runners-STL events to challenge even some of the most seasoned trail and ultra-runners! Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow - Lisa Kennedy at the finish showing off her new hardware!

Photo Credit: Matt Cecill - Finish Line, Fat Dog 120 Hard things are hard. It’s day two, and after 28 hours of running I find myself deep in the pain cave. My watch is reading 78 miles, and I have yet to come across Hope Pass Aid Station at mile 76.9. I’m trying to push hard up yet another very steep, never-ending hill, and I find myself dehydrated and low on calories. I’m lightheaded, dizzy, and my feet feel like they are on fire. ‘She Talks to Angels’ is blaring through my headphones. She never mentions the word "addiction" In certain company Yes, she'll tell you she's an orphan After you meet her family She paints her eyes as black as night now Pulls those shades down tight Yeah, she gives a smile when the pain come The pains gonna make everything alright…… I ponder in my head if this song was written for me; surely many others have thought the same. I press on as I focus on getting to the aid station. Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow - Approaching Hope Pass Aid Staion Like many of the other runners, I signed up to run Fat Dog 120 in 2020. And like most events out there, this race became a victim of Covid. So, two years of cancelations later, on August 4, I found myself at the pre-race meeting in a room full of runners at Manning Park Resort, BC. Somewhere between the nervous chattering, faint laughs, and infectious pre-race energy, we were told the race re-route would add more miles to the actual distance we’d be running race day. Fat Dog 120 will now be Fat Dog 123, but as we all know trail miles are approximations. The question that resonated in my head was “How much longer?” I knew when I had signed up that this race would take me well out of my comfort zone. I had only ever covered 108 miles in my previous 100-mile races. Unable to wrap my head around all the logistics, I focused on a text I had received earlier in the week from friend I had only met two weeks earlier while volunteering to course sweep for Hardrock 100 in Colorado. The text read, “Have fun and stay in the moment! The light is always there if you remember to listen.” It was followed by these lyrics from ‘Closer To Fine’ by The Indigo Girls. Well, darkness has a hunger that’s insatiable And lightness has a call that’s hard to hear This good luck text became my race day mantra, and for that I thank you, Michael Chavez! I held onto this the entire 127, that’s right… 127 miles that I ran. I chose to stay in the moment even when the going got tough and I questioned my ability to complete what I had started. Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow - Some shots from the start of the race My partner and my crew, Marcus, drove Chuck Collins, a good friend and St. Louis ultra-runner, and me to the start line of Fat Dog 120. Chuck and I began our journey into the unknown at 10am Friday. We agreed to pace with each other and run as much of the race as possible together with the understanding that neither one of us will hold the other one back. But you see, agreeing to run with someone else puts you in a precarious position as at some point both of us would be running the other person’s race. This was not something I was used to. Like everyone else I take my highs and run them until I hit a low, then repeat. There is no way to coordinate those highs and lows with another person when you choose to run with them. Going into Fat Dog 120, I had a lot of self-doubt… not because my training wasn’t all there, but simply because each time you find yourself at the start of yet another 100-mile race, you are journeying into the unknown. The outcome is never guaranteed. I had no real time goals except a best-case scenario of somewhere between 40-45 hours finish and a worst-case scenario to finish within the 48 hours cutoff. Photo Credit: Matt Cecill - Crossing Pasayten River Start – Pasayten River Aid Station Almost immediately we start with a 4,800 foot climb to the Cathedral Aid station at approximately 10 miles. Both the climb and the scenery left me breathless; I was on fresh legs and felt invincible! Following the ascent, we had a 4,200 foot decent into the Ashnola aid station. It was late afternoon by the time we got there, and the infestation of black flies and mosquitoes was at its prime, along with rising temperatures. This was the first time since the start that we had seen Marcus, and I was thankful to have him along for this wild ride! A quick stop for food, bug spray spritz, and ice, and we were back to running. As we left Ashnola, I noticed that my GPS watch read 18 miles, but the race guide had this aid station at 16.8 miles. I was following the GPS course file that I had uploaded to my watch, so the variance in distance was a bit unnerving. I realized that I couldn’t rely on the aid station distances that were provided to us in the race guide. As we left the Ashnola aid station I wondered in my head, “How far to the next aid station?” Heading into Trapper, the third aid station, we were still climbing but making good time. By the time we made it to Calcite aid station, the bugs had settled down a bit and the sun was starting to set over the distant peaks. The course started to wear down on my legs, and we were only 30 miles into the race. I tried hard to focus on the present moment… the sunset, the gorgeous scenery, and the comradery of fellow runners. At this aid station both Chuck and I stopped to add a long sleeve shirt and grab our headlamps before continuing into the setting sun. While I was waiting on Chuck, one of the aid station’s crew who was dressed like a grim reaper offered me cold beer. I immediately refused and then followed up with, “What kind of beer?” I’ve never once in my 9 years of racing had beer mid-race, surely I wasn’t going to start now. As I stood on top of the mountain of one of the most difficult races I had ever tackled with 97 miles more to go, I surely wouldn’t drink beer. In that moment the little voice in my head reminded me to stay in the moment, and so I reached into the cooler and opened a can of SOL, the best damn beer I have ever tasted! I offered a beer to Chuck, who reminded me of an article I had shared on Facebook on the negative effects of alcohol during endurance events which was followed by, “No thanks.” I thought about it, threw back the rest of the beer in an instant, and told myself, “You will not relive this moment, so do what feels good.” The cold beer felt heavenly! The sun had set and the temperatures were dropping by the time we descended to the Pasayten River aid station. The light from my head lamp revealed the river. I took my first steps into the water; it was cold and moving fast. The water in the river was at my knees as I struggled to find my footing while also trying to hold on to the rope overhead. I stumbled hard and almost lost it. I was waist deep into the river. Fact: I don’t swim, and I was panicking. I tried hard to focus on where I stepped, grasping at the rope. My heart was racing so hard, but I had made it across the river. I was in a bit of a shock and trying to process what had just happened. What if I had lost my grip? While I was still pondering on that what if, from somewhere in the dark I heard Marcus call out for me. This was the moment I reminded myself of something I get told by Marcus repeatedly. “One can’t continue to live their life with what-ifs.” It was time for me to let go of the question in my head, “What if?” Next stop, the Bonnevier aid station at 41.3 miles.  Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow Bonnevier – Hope Pass Aid Station Bonnevier aid station was only the second major, crew accessible aid station, and I was looking forward to changing my wet shoes and socks and getting enough food and fluids in me before we moved onto the next three minor aid stations. Not only were these next three aid stations remote and had limited food and water supplies, but they were also further apart in distance averaging 9.6 miles between them. The next major aid station was at Hope Pass, which wouldn’t be until 77 miles in mid-afternoon the following day. Little did I know this 33-mile stretch would test every ounce of my fitness and my mental fortitude. By the time Chuck and I made it to Heather aid station at 51.5 miles, not only was my GPS watch reading 55 miles, but it was also the middle of the night, windy as hell, and temperatures had taken a nosedive into mid-30s. We stopped to add more layers, gloves, and long pants. In the short period of time, it took us to do so, we were both shivering as we headed out without any food to grab at this aid station. Due to the remote nature of these minor aid stations, the volunteers had to hike in the supplies. By the time Chuck and I got to Heather aid station the first time, they were all out of hot water/broth and we had to wait a while for the volunteers to prepare hot food. I was growing increasingly hypothermic at this point, so we decided to grab some gels and press on to the Nicomen Lake aid station in the hopes that we’d be able to get some hot food and refuel there. By the time we hit the Nicomen Lake aid station, it was dawn and once again the aid station didn’t have any food prepared ahead of time. I was lethargic, and it was pretty apparent that I would need real food if I were to continue moving forward. I decided to wait for the volunteers to prepare some ramen for me. I was given a cup full of luke-warm water and dry-crumbled ramen. I needed real food and didn’t want to wait for the ramen to fully dissolve, so I asked if they had anything else to eat. I was offered a cold slice of fatty bacon. I felt lightheaded; I needed food. I sipped the water and pitched the rest, as I grabbed two more gels and we carried on to the next aid station. I could feel the fatigue taking over, and the lack of food and water intake had slowed down my pace considerably. By the time we hit Granger Creek aid station, I felt fried but the volunteers at the Granger aid station had broth and other pre-prepared real food that was ready to go. I was finally able to throw down two cups of hot broth, saltines, and some fruit. The section from Granger Creek aid station to Hope Pass was incredibly challenging for me. We had a 3,300-foot descent that was followed by a 3,600-foot climb to Hope Pass aid station. It was mid-afternoon of day two, and the bugs had made their ugly return along with the intensity of the sun. I was low on calories, and with each step I struggled to stay up right as I was dizzy and nauseated. Hope Pass aid station was littered with the carnage of runners dropping. We sat and started the process of getting this train back on track! I could barely speak as I choked on the dust I had been inhaling pretty much since the start of the race. I hacked some gross stuff out of my throat and felt better after chugging down two cups of coke. I was surprised and ecstatic to see Marcus at this aid station! Per our pre-race crewing discussion, Hope Pass was not one of the aid stations he was supposed to meet me at due to the challenging nature of the road getting up to the pass. But he had hitched a ride with another runner’s crew and had been waiting for us to get there with my drop bag ready to go. Both Chuck and I changed shoes, refreshed water, and ate a few perogies. At this point, knowing that I had almost 30 miles to the next major aid station at Blackwall, I decided to pack extra food for the trek back through the limited minor stations. Hope Pass – Blackwall Aid Station As we left Hope Pass aid station, I felt like a new person. I was determined to finish what I had started no matter how long it took. It’s amazing what a little food, coke, cold water, and change of gear can do for your mindset. I put my music on and pushed the pace for us to get to Nicomen. The sun was once more setting by the time we approached the Heather aid station; we were officially going into the second night and hadn’t quite hit 100 miles yet. I stopped to marvel at the insatiable depth of the mountains, the glorious sunset, and the slow cool breeze that carried the sweet smell of the wildflowers covering every stretch of ground as far as I could see. But there was something else the breeze was carrying... my own stench. Just then I heard a low thrum. We had heard this low thrum earlier in the day when we had made the same trek from Heather to Nicomen, and Chuck and I had talked about it but hadn’t seen anything. There it was once again! I stopped to look around and saw a rustling in the field of wildflowers. Just then a Spruce Grouse scurried up the hillside to my left. I smiled and, in that instance, I was grateful for where I was standing, who I am, and what I was doing. Chuck and I both grabbed a gel at Heather and kept rolling to Blackwall aid station. The stretch from Heather to Blackwall aid station would have been ‘runnable’ had my feet not been trashed. To add to the agony, there was some technical terrain so I power-hiked until we hit the road. It was around 11:30pm on Saturday, Aug 7 when we hit the Blackwall aid station and my GPS watch was reading 104 miles. Once more I was ecstatic to see Marcus and my pacer Zarah Hofer! Chuck and I both sat down at Blackwall aid station. We added layers as it was starting to get cold again and ate a ton of food knowing that this was going to be the last aid station with some decent real food to eat. We needed to refuel for the last 27 miles. The state of my feet was pretty bad. I fumbled to patch up some blisters and change my shoes and socks. Less than a marathon to go! I knew it would be a long stretch with approximately 5,900 feet of descent and 4,200 feet of ascent over East Skyline Trail before I’d cross Rainbow Bridge and see the finish line. In that moment I reminded myself of what I had endured and what I needed to do to finish! At this point I knew Chuck and I had to part ways. I told him to go without me since I had a pacer, and I needed more time at Blackwall aid station for my feet. I felt a small tinge of panic as Chuck left, and I was about to start running with my pacer Zarah. Why a tinge of panic? Up until midnight on Sunday, August 7, 2022, I hadn’t met Zarah Hofer. I had never run with her and had no idea of who she was and vice versa. Up until 3 weeks prior to the race, I had a pacer lined up and ready to go, or so I thought until my pacer was injured and couldn’t pace me anymore. Upon the recommendation of some friends, I had posted a pacer request on a women’s only running group, “Ladies of the Trails” based in Vancouver. Zarah had responded to my post and was willing to tag along with me for the last 20 miles of the race and get me to the finish! Zarah and I had exchanged texts and a couple of phone calls prior to race weekend just so we could connect on some level and review pacing/running strategies. Somewhere in my rambling, I had mentioned to Zarah that the only time she could push me would be a downhill section. Outside of the simple task of getting me to the finish line, I had no expectations. Photo Credit: Zarah Hofer - East Skyline Trail Blackwall Aid Station to the Finish Line After what seemed like forever spent at this aid station, Zarah and I finally started on our trek so I could finish what I had started almost 40 hours earlier. The next 6.6 miles to Windy Joe’s flew by as Zarah and I talked and ran a downhill section on the road in the stillness of the early hours of Sunday morning. Even though every rock I ran over felt like a stab to my feet, I was running and heading towards what would be the farthest distance I would have run thus far. I grabbed a little food to eat at Windy Joe’s, and we kept rolling towards Strawberry Flats. Far out in the distance we could hear cheering and announcements for the 42 hour runners finishing the race. In that moment the two things that ran through my head were: One, I was going to finish this damn race and two, the 42 hours finish time was out, but could I still finish in 45 hours. Or at least I had to try! I repeated this in my head, and we quickly moved the 4.9 miles to Strawberry Flats aid station. At this aid station both Zarah and I made sure we had plenty of food and water to get us through the final 11 miles to the finish. Once we left this aid station, we started the brutal soul-crushing climb up the East Skyline Trail. Holy Shit! I can honestly say this was both physically and mentally the hardest section of the course for me. Just then we came to a halt and started climbing once again. With no end in sight, this trail segment was not only steep, but it was gnarly and technical. One misstep and death would be imminent. I tried hard to focus on continuing to move forward with encouragement from Zarah. I was 44 hours into the race, and my watch had already hit 123 miles which is what we were told the length of the race would be. How far was the finish line? Race courses that challenge us as trail runners is why we keep finding events like Fat Dog 120 to suffer! With this thought, I pushed myself hard as we slowly crested what appeared to be the last hills. We started running downhill. Could this be the final descent to the finish!?! My head was foggy, and I had lost all concept of time, thinking hurt my brain. I needed to be done. “Why was I hungry again? Now I’m hot. Why are we still running?” With all these thoughts rushing through my head all at once, I realized we were descending a very steep and never-ending downhill. I heard Zarah call back to me, “This is it! We are so close!!” I was running the downhill as fast as I could push my legs. We turned a corner and the Lightning Loop Lake Bridge Rainbow Bridge came into view. We could hear cheering. I almost broke down in that moment, but then I looked at my watch and saw I was 46 hours and 30 minutes into the race. There was no more time to be wasted with the finish line in sight; I ran hard! I saw Marcus running towards me as he cheered us on, and in a blink of an eye I found myself at the finish. Ok, ok, it wasn’t quite “in a blink of an eye”... more like 46:36:08! Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow - Post-Finish Zarah and Me Conclusion Fast forward to the day after my return to the USA and I find myself surfing the internet trying to find yet another adventure to self-inflict pain. Hadn’t I had enough!? I’m in love with British Columbia! Fat Dog 120 is a piece of heaven and hell that I got to experience over 48 hours and was by far the hardest race I’ve been fortunate enough to compete and complete. Fat Dog 120 was more than just a race, it was a much needed cathartic journey! So, I leave you with this: Hard things are HARD, but who you become at the end of that difficult journey is someone you should be proud of! Oh, I’m seriously thinking about moving to British Columbia. Not sure what I will do there, but you only live once! Photo Credit: Matt Cecill - Finish Line, Fat Dog 120 Special thanks to my one and only crew, Marcus and my pacer, Zarah. Photo Credit: Marcus Janzow - Post-Finish Chuck and Me Photo Credit: Zarah Hofer - East Skyline Trail

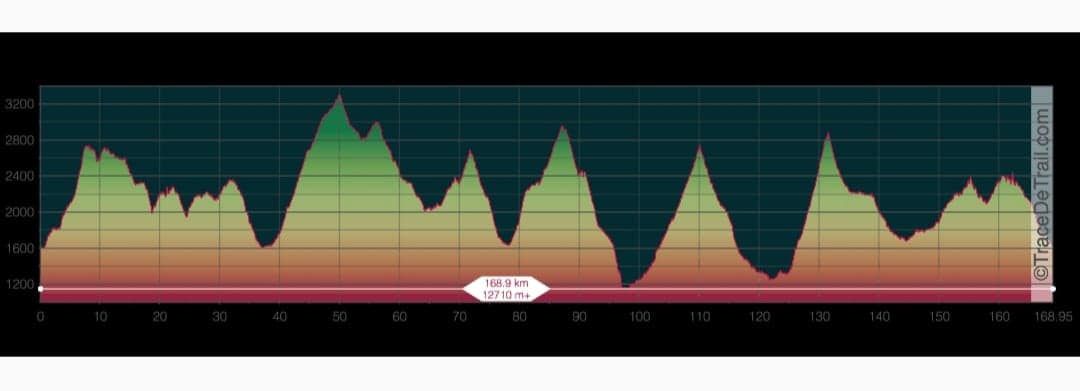

“Experience is what you get when you don’t get what you want”This pretty much sums my race at Ultra Tour Monte Rosa (UTMR). It’s been a week since the event, and there’s still a dull tightness in both my quads — like when you lift weights and are sore for days after. Just a subtle reminder of what ensued on Thursday, September 12, 2019. What is UTMR? Ultra Tour Monte Rosa (UTMR) Distance – 170KM (106 Mi) Elevation – 11,600 Meters (38,058 Feet) Altitude – Race starts at about 6,000 feet, goes up to approximately 12, 000 feet at the highest point, and then ends at 6,000 feet Race Report UTMR is a mountain race through and through! Which brings me to where I live: St. Louis, Missouri, 535 feet above sea level. What in the world would possess my flatlander arse to pick this race? Simple answer: Impending failure, or to put it another way, I wanted to see how close to the edge I could push myself before crash and burn happened. (Yeah, I like that better. Let’s go with that!) You see, there is something extremely beautiful and gut wrenching about willingly doing something that has failure written all over it. But, like most things in life, when 99 percent of the times things fail, there is that 1-percent chance that you could succeed. So, I had that 1 percent going for me! Sometime in mid-summer of 2018, I was talking to Jason Poole, a good friend of mine, as I counted my points to enter UTMB and immediately turned to tell him I couldn’t. My reasoning: Too many freakin’ people; I wasn’t sure I wanted to deal with 2,300 people and the circus it would cultivate. Jason’s response: Don’t do it! Followed by, “You should run UTMR, you’ll like it. It’s B.R.U.T.I.F.U.L and only 300 runners!”  Birds eye view of Grachen Birds eye view of Grachen I had been following UTMR for a few years but never really thought I’d run it. Conversation with Jason ended, and I scanned through the UTMR website. I looked at the pre-registration requirement for the 170 KM Ultra Tour, and I had not run any of the races listed, but I had run Cruel Jewel 100 the past May and that was going to be the race I was going to qualify with. Cruel Jewel 100, although not a mountain race, still gets 33,000 feet of gain and 33,000 feet of drop, so that is what I had — plus the few 100-mile mountain races I had run in the USA to qualify me (I hoped). Right around then, I sent Luigi Terzini, another friend of mine, a note asking him if he wanted to run UTMR. Luigi is from the region, so I thought maybe he’d join me — and just like that Luigi was in. Fast forward January 2019; we both applied as soon as the pre-registration for UTMR opened. Then, we waited and waited until one afternoon I got the email confirming I had been selected to run UTMR in September 2019. And as did Luigi. Exciting stuff! The next eight months revolved around mandatory gear list, passports, coordinating flights, hotel accommodations, and an endless back and forth of emails, texts, and phone calls between myself, Luigi, Jason, who also decided to join us, and Martien Vadersmissen. Martien is a good friend whom I met in St. Louis while her family had relocated to USA for work. Since then, they had moved back to Switzerland and she became a liaison for Luigi and me with race preparation and logistics. It was like the universe was working in my favor. Everything just seemed to fall into place! Except, I had been nursing a peculiar acute pain in my right heel for which I had seen a few specialists. Eight weeks of rehab later and the diagnosis wasn’t clear, but I continued to train as the decision to run UTMR had been made regardless of how much of a pain in the rear my heel was being. I won’t bore you with the details of my training — just know that I climbed a LOT! Sometime in July 2019, I finally found out that I had a bursa at the insertion point of my Calcaneus and Achilles. Per doctor’s orders, no eminent damage could come from running UTMR except I’d need to manage the pain that came from climbing and some downtime was in order upon my return from the race. Pain is relative when you run distance!  Lake Geneva with Luigi and Martien Lake Geneva with Luigi and Martien On September 1, my bags were packed and Luigi and I boarded the plane to fly to Geneva, where Martien was picking us up. We spent a couple of days exploring Lake Geneva before we made our way to Grächen to check-in and prepare for the race. Mandatory gear check, bib number, and tracker collection later, Luigi, Martien, Jason, and I met up for some pizza and beer before calling it a night. I was nervous! Luigi and I got back to our sleeping quarters and started to lay out gear for race morning. As I pulled out my bladder to fill it up with water, I noticed my pack was soaking wet. Upon close inspection, there was a hole in my bladder from which the water was leaking. I panicked! Luigi suggested I empty, dry, and tape/patch the hole in the bladder before filling it up again. I did as was suggested and went back to fill the bladder for the second time. It was still leaking! WTF!?! Had I taped the wrong side? Looking at the bladder closely, I realized the hole went in one side and out the other. So, I repeated the empty, dry, tape process and filled the bladder up for the third time. The bladder seemed to be intact and hold water just fine without any leaks. The little voice in my head: How long will this hold? I guess we’ll find out tomorrow, as I start to run.  After the usual restless night of sleep before any big race, the alarm went off at 3 a.m. Thursday, September 5. Bladder check and last-minute prep. Then, we made our way to the town center for the race to start. A couple of things were grinding on me: I felt overdressed, my pack was particularly heavy with all the mandatory gear, water and fuel, and the most unnerving thing was the weather forecast for the race that had gotten progressively worst, calling for rain, sleet, and snow during the first night into day two of the race. It will be what it will be! After a quick pre-race photo, Jason, Luigi, and I exchanged well wishes. Just like that, the race had started. Both Jason and Luigi took off as I moseyed my way with the mid-pack from the start line into the dark, foggy, and chilly morning. The first 10K of the race was a bit of a blur, as I focused on my footing in the dark and staying steady with the rest of the runners that I found myself pacing with. Then, it began!  Black and white Swiss Mountain Goats and NO I did not take this photo Black and white Swiss Mountain Goats and NO I did not take this photo We started to climb. It was still dark, trekking poles came out, and in the beam of my headlamp I could see my breath as we ascended 4,300 feet in just a couple of miles. It was a never-ending climb! I remember internalizing to brace myself, as the worst is yet to come and I could do this just as long as I keep moving, one step in front of the other is all it takes. I needed to make the cutoff to Zermatt and then just keep plugging at it. By the time I neared the top of the climb, the first light of day had slowly begun to peer through the mist and fog. I stopped at the top to fill up my handheld with water from one of the springs and chatted with a few of the runners as they made their way up. As I began to run once again, I fell behind Erwin Bennett from Panama City. He joked about how he thought he had trained for hills, yet that climb had just about done him in. I stopped to take photos and Erwin peeled away. The scenery before me was truly breathtaking! I found myself running alone through meadows surrounded by mountains and in that moment, I stopped, closed my eyes, and I took a deep breath. This was my “the hills are alive with the sound of music and my heart wants to beat like the wings of the birds” moment! But the moment was short lived, as I heard some bells in the distance, fast approaching. As I slowly turned to look in the direction of the sound, all I could muster was, “Whaaat!?!” There was a herd of about 15 Swiss mountain goats heading toward me. Oh shit! They really were CHARGING right at me! I started to run, and they switched directions from the hills to follow me. In a state of sheer panic, I found myself no longer running on the trail but headed straight for the drop, and the realization that pretty soon I was going to run out of ground space and perhaps fall to my death or have to fight of the heard of goats quickly gaining on me. There was no out running them. Just then, another runner came bounding around the corner and the goats stopped, a bit distracted by the added human presence. The runner stopped as he noticed the scene before his eyes, I yelled out to him and hoped he spoke English. Me: I don’t know what to do? They are charging at me. Runner: You have to yell at them. They want to fight you. So, yell out loud at the goats. Me: Umm….OK. I’m not sure what I yelled, but I was banging my trekking poles and spouting out gibberish as I walked in the direction of the goats. Survival skills everyone should learn: how to scare mountain goats charging at you in the middle of nowhere! Just like that, the goats began to retreat and then took for the hills. I jumped back on the single-track and ran as fast I could, not stopping until I hit Europahutte aid station (17.1km). I don’t remember what time it was, nor did I care. I filled up my water, grabbed a banana, and was in and out of that aid station.  The next stretch of the course was a bit treacherous, with three bridges and narrow stretches of rolling single-track cut into steep hillsides. But the views were incredibly breathtaking. The fog had cleared, and some sunlight and clear skies made it possible to see the vastness of where I was. The unmoving mountains in the distance stood towering all around, and in that moment I felt miniscule. Past the first two rickety bridges, I fell in line behind Elaine Stypula, who was from Michigan and knew Jason. What are the odds? Of the 266 runners that started the race, only 10 of us were from the USA (and only four women) and here I was running with one of them — and to top it all, she was a fellow Midwesterner. I don’t remember much of this section of the course, as the miles went by quickly while Elaine and I exchanged stories. I realized perhaps I could hang with Elanie and we could both push each other and get through the night hours and perhaps finish together. We both hit Taschalp aid station (26.4km) and were informed we had an hour and a half to get to Zermatt, which meant we had to run 10.4km with enough time for gear change, grab micro-spikes to cross the glacier, and refuel to be ready for the night stretch. I was famished by the time I hit Taschalp, and I threw down a couple of cups of broth and bread, grabbed a banana, and headed out towards Zermatt with Elanie. As we traversed the downhills, I noticed Elaine would fall behind, but she would catch up to me on the uphills and I would struggle to keep up with her. Before we made it to Zermatt, there was the Charles Kuonen Suspension Bridge to contend with. I recalled a conversation with Jason prior to the race when he had asked me if I was afraid of heights. My answer was no, but as I stood at the edge of the Charles Kuonen Bridge, I wasn’t too sure anymore. The longest pedestrian suspension bridge in the world is almost 500 meters long and 85 meters above the valley at its highest point. GULP! Just don’t look down, I told myself. I slowly began to walk towards the other end, which looked like a spec from where I was standing. Somewhere on the middle of the bridge, I made the mistake of taking in the scenery around me. Everything seemed frozen in time, and I panicked. I felt vertigo and nausea about to hit me. I hurried toward the other side of the bridge and, once I got there, took a moment to collect myself. I did not look back once.  Just then, Elaine came up behind me and as we played catch up with each other, we made our way to Zermatt — 30 minutes ahead of the cutoff. Zermatt was a runner’s graveyard. So many runners had decided to drop there, and I knew there were a few behind us that would not make the cutoff. As we rolled into the aid station, I lost Elaine, since she had a crew waiting for her there. She was in and out of Zermatt before I finished unpacking and then repacking my pack for the next stretch until Gressoney, where I would have access to another one of my drop bags. I wanted to stay with Elaine, but I also realized I need to make sure I had packed everything for the next stretch of the race. In that moment, I wished I had a crew! While I was changing my socks, I chatted with a few runners who mentioned the next stretch on the race was much harder but the cutoff would ease up. They bid me goodbye and headed out. While I was trying to wrap up everything, I got up to get some food and noticed a substantial drop in temperature. The wind had picked up, and there were flurries in the air, so I went back to my drop bag and grabbed another jacket. As I sat there futzing with my things, a volunteer approached me and said I had 10 minutes to get out of there and to make sure I had all mandatory gear, as reports of fast-approaching bad weather were coming in. Time was slipping away, and I hadn’t even eaten anything. I had no time to eat, so I ended up dumping the food, grabbed a piece of bread and headed out of the aid station. I was hungry, but there was no time to hang there. As I made my way through the town of Zermatt, a mountain resort town that lies below the iconic Matterhorn peak, the streets were bustling with tourists and people leisurely killing the afternoon. While I navigated the course markers through the town’s streets, I couldn’t help but wonder what the hell I was doing. Why am I here? I could be sightseeing but instead I’m lugging around the very heavy, extremely uncomfortable pack, my quads are on fire, I’m hungry, and the smell of food as I passed the restaurants was not helping my mental state. I pressed on and tried to enjoy the scenery before me as I made it back onto the trail. As I headed up a steep climb, I came upon Erwin. I didn’t expect to see him there, but I guess like myself he wasn’t doing so hot. We started to pace together and chatted as we slowly climbed our way towards Gandegghutte. This seemed like a never-ending stretch! I was starving, low on calories. It had started to rain, which soon turned into sleet, and I could feel the cold in my bones. Ervin and I both stopped to put on our waterproof gear, and I threw down a bar and some cashew butter. Another mile later, Erwin announced he was feeling sluggish and had to dig into his emergency food ration. He sat on a rock to collect himself while I pressed on. I was about ¾-mile from Gandegghutte when I saw a conga line of runners coming down the trail towards me. In a state of confusion, I stopped and called out, “What’s up?”  It was a group of Spanish runners that tried to communicate to me that I needed to check my phone as they ran past me. I pulled out my phone and saw a few texts from the race organizers: weather reports followed by the dreaded message, “Race is cancelled due to inclement weather/snow and runners should make their way to the nearest check point.” Ugh! Should I try to go to Gandegghutte and take the ski lift into Zermatt or should I simply run downhill back to Zermatt? Screw it! I decided to bomb the downhill instead. Trail conditions were getting slick; sleet had turned into ice, and there was a dusting of snow starting to line the single-track. Just then, I ran into Erwin once again. We both decided to make a B-line for Zermatt instead of following the original trail that we had climbed out of town a couple of hours earlier. By the time we got back to Zermatt, I was soaking wet, cold, and shivering. When we got to where the aid station was, there was nothing but a canopy left, along with three other runners we took cover and that’s when slowly other runners started to make their way back to Zermatt. A thing I learned about international races is, when you put a bunch of runners that don’t communicate in the same language and the race gets cancelled, panic, confusion, and loud multitudes of language overload sets in. As important as language is for communication, it also creates barriers and divides people. In that moment, as we all tried to keep our shit together, I wished I spoke French or Italian or perhaps Spanish — anything other than just English and my mother tongue, Hindi. We finally got word that someone was headed in our direction to help us get back on a shuttle that would then take us to Grächen. It would be another 30 minutes before we could get a ride out of Zermatt. I was starving, and all I wanted was a cold beer, so Erwin and I ran back out into the cold rain to the grocery store a couple of blocks away from our base tent to get some food and beer. At the grocery store, we found beer — and for the record, beer is BEER in any language! Then, an argument erupted over a hot sandwich, which to me looked like a chicken sandwich and Erwin claimed was a fish sandwich instead. Neither one of us could read French, so back nor forth did we go until I overheard another shopper call out to her son in English. I grabbed the sandwich and asked the woman to help us decipher exactly what kind of sandwich it was that we were about to devourer. It was a chicken sandwich! We checked out and inhaled the food even before we got back to the tent, and as we stood there drinking our beer, I offered the extra beer to another runner by the name of Enrico Romano from Italy. Enrico accepted the beer and then the below conversation ensued. Enrico: Hey, you are the one my friend Marco saved from the goats. Me: (spitting out my beer) Umm…Yeah, that was me and let’s not talk about that. We both laughed at that and said cheers as we drank our beers! At some point, about 40 of us walked to the bus station at Zermatt and boarded the shuttle back to Grächen. It was dark, and there was an eerie silence during the shuttle ride back into town. Erwin and I walked together to our quarters, as we were staying the same building. We said goodnight, and I remember looking at my watch. It 9 p.m., and I was freezing. After cleaning up once my brain had thawed out a bit, worry started to set in as I realized Luigi and Jason had not yet made it back. They had both been well ahead of me. A few texts with Martien later, I was told that she was driving both Jason and Luigi back to Grächen. I was relieved to hear they were both alright, and I crawled into bed. Luigi got back to the cabin sometime around 3 a.m., and we exchanged a few words before we both passed out. Just like that, it was a new day and the race was over! The next morning, we packed up our bags, dropped off the timing chips, and checked out of the cabins. I saw Erwin, and we exchanged contact information as we rolled out of Grächen after saying bye to Jason. Martien, Luigi, and I headed back to Montreux. The next few days were spent with Martien and her family as we visited Montreux, Vevey, Lake Geneva, Lausanne, and Gruyeres while doing all the touristy stuff. We spent our last day in Geneva sightseeing before catching the flight back to the USA. Conclusion

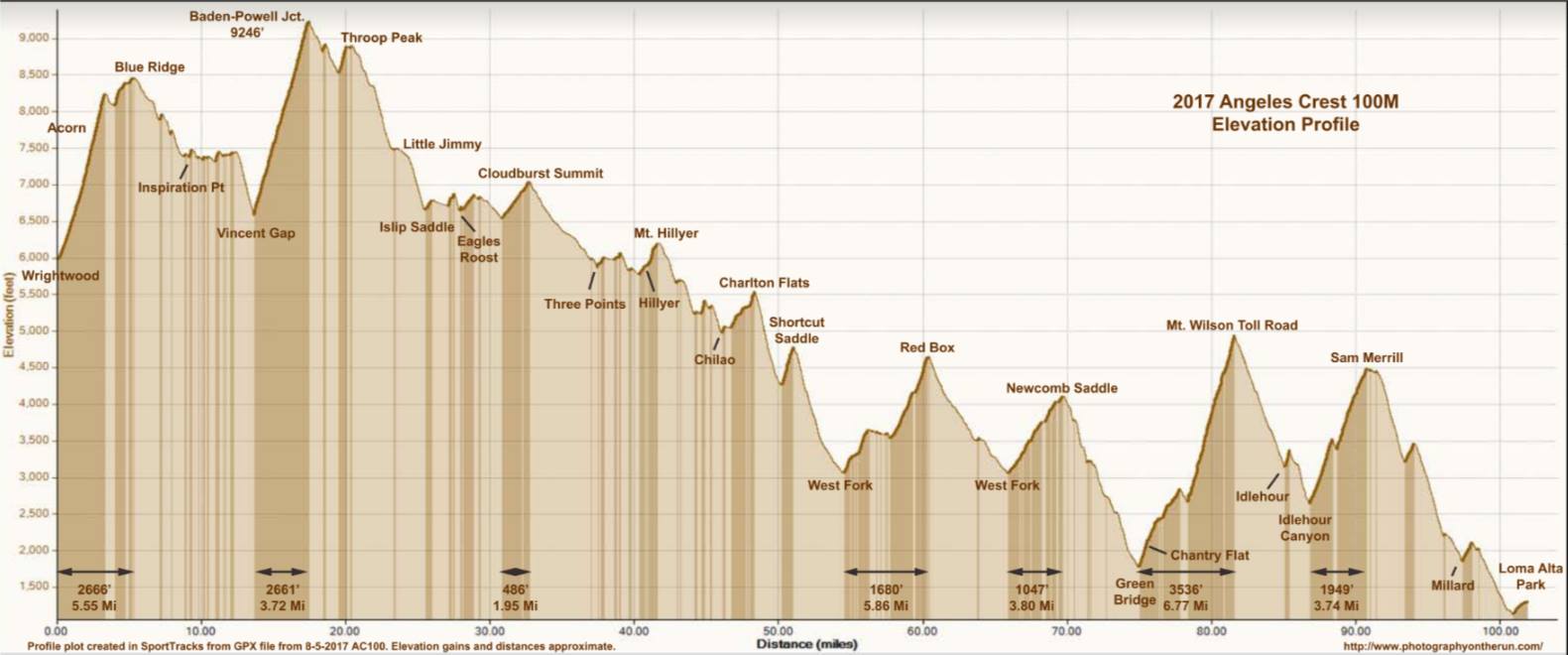

It’s hard to describe my experience and how I feel. There is a lingering feeling of incompleteness. What if? Would I go back and finish the race? Will there be a different outcome the second time around? How bad do I want to run UTMR? There are a lot of mixed emotions and feelings: a longing of sorts, maybe not so much to finish but to be able to see what lay ahead of me and perhaps a finish line seal. The end is what we all strive for — conclusion, closure — but perhaps some things in life are better left unconcluded. There was so much beauty, simplicity, towering mountains, and unrelenting terrain that it’s hard to not have an end to this race. In the short 35 miles of the course that I got to run, I fell in love with this race; the Alps don’t compare to anything I’ve run here in the USA. So, to answer the question of going back: it’s a bit complicated. I want to go back, but sometimes, time is just not in our favor. Maybe I’ll have another opportunity to run in the Alps some day! Picture this: A car coming to a screeching halt, exhaust fumes everywhere and nothing but pure burn. “Can you breathe,” I hear someone ask. I’m disoriented, unable to respond. My eyes search for Amanda, my pacer. There is a mixture of exhaustion, adrenaline, euphoria and the question ringing in the back of my head: What the hell just happened? I see Amanda. I’m crying. I give her a hug. The next thing I know, I’m sitting in a chair, my lungs are on fire and I’m having trouble regulating my breathing. I hear someone say, “Call the medic. Her mouth is purple, and she’s having trouble breathing.” An ice pack drops on my head, cold water pours over me, and someone shoves a cup in my hand and tells me to drink. Then I hear the medic, “Can you breathe?” Me: “Yeah, I just need a minute.” The guy is standing there, watching me. Me: “I’ll be fine.” I’m not sure how long I sat there before I realized the clock had struck 2 p.m., and, as I look up, Wanderley Reis comes across where the finish line of the 31st annual Angeles Crest 100 (AC100) used to be just 7 minutes and 46 seconds before. Wanderley had missed the 33-hour cutoff. I’d hopscotched the last 50 miles of the race with him and his pacers, and I couldn’t understand how he had missed the cutoff. I was devastated for him! This is the year, I had said to myself. I’m going to push every physical limit while I’m still able to do so, and here I was sitting on a chair after having crossed the finish line in a time of 32:55:20. Never before in my five years of ultra-running had I had to chase cutoff. This was a new and interesting feeling. My journey to AC100 began in August 2017, when on a whim I had entered the lottery for the 2018 race knowing little more than it was a classic and I wanted to check it off my “to do” list. Ever heard the saying “What you seek is seeking you?” Fast forward to August 2018. I’m nursing Achilles Tendinitis coming off a rollercoaster year with some of the hardest ultras out there. I’m questioning my sanity, but, still, I begin to prepare for AC100. My crew and pacer Amanda Smith and I get to Wrightwood, California, on Thursday, August 2, and find out that logistics for crewing and pacing at AC100 are just nuts. Amanda assures me we’ll make it work! Opening Credits Race: Angeles Crest 100-Mile Endurance Run Race Directors: Ken Hamada, Jakob Herrmann and Gary Hilliard Location/Course: Race starts at downtown Wrightwood and ends at Loma Alta Park in Altadena, California. While the runners find a way to thrive on the high alpine ridges of Baden-Powell summit at 9,300 feet, the rocky trails of high country, and the deep canyon surrounding Mt. Wilson. The terrain is extremely technical, with a mix of rocks, roots, lots of loose dirt and ridgelines as you traverse sections of the single-track trails and a solid mix of pavement. It’s HOT! Thrown into the mix is 21,610 feet of cumulative climb and 26,700 feet of descent. The ascents are steep and the descents even steeper! Difficulty: AC100 is considered one of the more challenging running event in the world! Time Limit: 33 Hours Runner: Shalini Kovach Pacer/Crew: Amanda Smith Goals & Training: Coming off Cruel Jewel 100 at the end of May, followed by Cry Me A River 100K in July, I had ample training for hills and heat. (Or so I thought.) My goal for the race was to finish in 30 hours, but this isn’t my first rodeo, and I always stay fluid with my running “goals.” Ultimately, I wanted to come home to St. Louis with a buckle. Finish before DNF, because DNF sucks.  Race Report Start (0.0 Miles) to Islip Saddle (25.6 Miles) The race began at 5 a.m. on Saturday, August 4. I don’t remember much other than I said goodbye to Amanda and the next thing I knew we were climbing. (The uphill trek had begun within the first half-mile of the start line.) It was still dark, so my head was down. I was eerily aware of my heart rate and my slow hiking pace as we climbed from 5,942 to 9,260 feet within the first 16 miles. When I finally looked up, the sun was rising in the distance — Blue Ridge in all its morning glory and the promise of a gorgeous day ahead. I needed to steady my breathing in order to be able to run the downhill, as I was clearly sucking on the uphill. By the time I hit Vincent Gap aid station (13.8 miles), my breathing had settled a bit and I was running steady. I filled up my water, because the next aid station at Islip Saddle was 11.4-mile trek and the sun was starting to beat down on us. Soon after leaving Vincent Gap, I found myself at a standstill while I waited for the first rattlesnake of the day to cross the trail in front of me. Onwards! About 1.5 miles before I hit Islip Saddle, I had drunk through my entire 16-ounce handheld and 2-liter bladder and was completely out of water. WTH!?! At this point, I was well ahead of my projected 30-hour finish pace, and, despite being hot, I felt good. I saw Amanda at Islip Saddle, filled up my water, refueled and once again began to climb.  Islip Saddle (25.6 Miles) to Chilao (44.4 Miles) In short, everything in between Islip Saddle and Chilao pretty much sucked. In length, this is the section when all hell broke loose. We hit several sections of pavement on the highway, weaving in and out of dirt trails, then pavement again and no tree cover. We were baking. Baking well! Technically speaking, I should have been able to make up some time running on the pavement and its lighter inclines, but the heat rising from the asphalt could be seen from a distance. No amount of ice or water helped. It felt like hell, or what I imagined hell would feel like as I tried to divert my brain from going into a dark place. In my head, it sounded like this. Me: I don’t ever want to go to hell if this is what hell feels like. Myself: Maybe there are tiers in hell. Tiers of HOTNESS. I: Tiers or not this is HELL! Damn it, my ink is getting burnt! I tried to make myself run from one siderail to the next on the road, then hike in between. At some point, my brain just gave up and I started a death march on the pavement, not giving two shits about my pace and time. I just need to get through this and wait for the sun to go down to pick up pace! Chilao (44.4 Miles) to Chantry (74.0 Miles) By the time I got to Chilao, I was an hour ahead of the cutoff at that aid station and fully aware of the fact that my so-called 30-hour finish goal was currently hanging in the balance of “get your shit together” and “get the hell out of this aid station.” I saw Amanda at Chilao for the last time, knowing the next time I would see her would be at Chantry (74 miles), where she would be jumping in to pace me for the last 26.2 miles to the finish. I was in and out of Chilao, stocked up and ready for the sun to go down. Some of my better running happens at night. I’m much more in tune with myself and can focus on powering through. Plus, I figured the drop in temperature would help me make up some time, so I was looking forward to hammering the run and hopefully getting ahead. Shortly after leaving Shortcut (50.7 miles), my headlamp was turned on and I was starting to enjoy my run as I marveled at the sunset and the expanse of where I was. I couldn’t help but think how miniscule and insignificant we are when thrown against nature. One misstep and I could be engulfed in the nothingness of the mountains! The miles went by fast, and as I ran hard down a tight switchback I suddenly noticed that I wasn’t alone. In front of me stood Cesar Salas and Tristan Jones, both of whom I had chatted with earlier in the day as we hopscotched each other during the race. Me: What’s up guys? Tristan: Rattlesnake! Me: That’s number two for the day! After the snake had crossed the trail, we started to pace together and a few minutes later I broke away from the boys and kept rolling down a steep descent. But it was soon over, and I was hiking a steep hill when I heard someone behind me. It was Cesar sitting down on a rock. Me: C’mon man! Don’t sit. We have got to keep moving. I was fully aware of the fact that sitting at this point in the race would be futile, and time was not on our side. So, just like that, Cesar, Tristan and I became the three musketeers. By the time we left Red Box (59.3 miles) I was starting to feel some hot spots at the bottom of my feet and reluctant to accept that I was nursing some massive blisters. Just then, we passed Morris De La Roca. I was so focused on running that I didn’t even notice that Morris had no headlamp. I heard Cesar exchange a few words with him. I asked Cesar what was wrong, and the long-short of it was that Morris’ headlamp was out of battery and he feared being disqualified if he asked for help. As a result, he was now “running” in the light of his cell phone. Me: Huh!?! That’s crazy! Cesar and I waited till Morris caught up to us, and we asked him to run in between the two of us until he got to the next aid station and could ask for batteries there. We finally made it to Newcomb (67.6 miles)! I sat there while the aid station crew helped me patch up my blisters and change my socks. As I contemplated whether to change my shoes or not at Chantry, I heard someone say the course sweep were at Newcomb already. Sheer panic set in! What!?! Me: How far ahead of the aid station cutoff are we? Cesar: One hour! We are waiting on you, let’s go. Me: Don’t wait on me, not sure I can keep up. My feet are done! Cesar: Let’s go! So, with that, Cesar, Morris and I were back on the trail while Tristan tried to piece himself together. Every step felt like a stab, and I just couldn’t hot-step the downhill as fast as I would’ve liked. As Cesar and Morris broke away from me, I knew I would be running alone once more. But I was looking forward to picking up Amanda at Chantry, so all was not lost just yet. Chantry (74.0 Miles) to Finish (100.2 Miles) “You Can, You Will.” That was what was written on the pavement as I turned the corner to Chantry, and that was what became my mantra from Chantry all the way to the finish. I saw Amanda at the aid station, ready to roll. I filled up water and food and tried to eat while the medical team worked on my feet again. Time was ticking away! Chasing cutoff is not conductive to effective stress management, and I knew getting my feet patched and changing my socks and shoes had eaten into some of the time cushion that I had when I rolled into Chantry. By the time Amanda and I hit the trail again, I was 40 minutes ahead of cutoff. We were anticipating the last 25 miles to be the hardest, as I had heard all day Saturday from some of the veterans on the course. I wondered how hard this section could be. We were about to make the infamous climb to the “Dead Man’s Bench.” Aw shit! That’s right, I thought I had died and gone to hell for sure. Dead Man’s Bench was graced by my rear, and I sat there taking in the marvelous view. It was worth it! I didn’t sit there for too long, though, as I was aware of the time constraints, so we climbed some more. It was Sunday morning, and the air was still a little cool, so I hammered the downhills like a mad woman, hitting a 7:55 pace. I could feel the blisters in my feet pop. I didn’t care! Quick stop at Idlehour (83.4 miles). I had made up some time, but not enough to stop and lollygag. We hustled to climb once more. The temperature was hitting 97 degrees, the trail was exposed, I could feel dehydration setting in and I was running out of water again. It felt like I was on fire. I was having trouble regulating my breathing, and, pretty much since having left Red Box, I had been hacking and coughing dusty mucus. At this point in the race, my lungs were shot. I was acutely aware of the tightness in my chest that had gotten worst. Sam Merrill (89.1 miles) was a blessing! As I sat there, I was doused with water, ice dumped in my buff, sunblock sprayed all over my body. Sam Merrill was like a mad lab of volunteers! Fully stocked and ready to hit the trail once again with Amanda in lead, my brain just felt like soup. Hot boiling soup. Sigh! I can’t do this anymore. I think I tried to speak, but I couldn’t form any words. “We have to run” is all I heard Amanda yell as she continued on a really technical downhill switchback. I rolled my ankle three times and stood at one of the switchbacks with tears building up in my eyes…or was it because I was squinting so hard that I had lost all depth perception on the trail? There was no telling what was happening. I felt like I had lost all control. The combination of heat, sun, dehydration, fatigue and blisters hurt. Everything hurt! Just then, we had to stop again for a snake. C’mon! By the time I rolled into Millard (95.6 miles), I had officially lost my shit. Everything was happening so fast. Volunteers at the aid station were talking fast, my head was spinning and then I heard Amanda. “We are 7 minutes ahead of cutoff at this aid station and we can’t stop.” I needed to stop. I was crying, either in pain or shock or at the enormity of the task that laid ahead: 4.6 miles of running in an hour — not hiking, not walking, just running hard to the finish. I have never felt so broke down in my life, and everything was out of my control. All I remember saying was I can’t breathe. Before I could utter another word, Amanda was off again and edging me to follow. I wanted to yell and say I couldn’t and I wouldn’t, but I knew that was bull. “You Can, You Will.” I repeated those words in my head, and we ran. We ran hard! Amanda and I turned the corner to the last 1.2 miles on pavement and I could see Yoshio Otaki struggling to run about a quarter-mile ahead of me, he was chasing cutoff just like I was. It can’t be, I wanted to scream. This isn’t right. Why can’t I breathe? My legs felt fine, my brain was operating on adrenaline, but my lungs were just about giving out on me. Just then, Amanda turned to look for me. I was stalled. Amanda: You can’t stop, not now! You need to run! Don’t freakin’ stop! You have to finish! I could see the panic in Amanda’s face, and all I heard was yelling. “Let’s go, 3 minutes.” I ran. I have never run so hard in my life except for when I’m angry. It was anger, it was fatigue, it was madness, and it was running like my life depended on it. Conclusion “It’s only running” some will say, not life or death. Choosing to quit is easy, but in choosing to continue moving forward, knowing that the odds are stacked against you, there is a rush like no other. It’s been over a week since I crossed the finish line for AC100, and I can still feel the tightness in my chest when I run. I’m still coughing up mucus. Is that weird? I’ve caught myself asking that multiple times. I can’t explain what happened, but when I look at the race results and see that only 100 of the 190 runners who started the race finish it, I feel good. I was one of the 100 runners who got to experience the “golden moment wrapped inside the exhaustion,” and I get to savor it. There is a time for holding onto and there is a time for letting go. AC100 was my time to hold onto. There will come a point in my running career when I will have to let go, because we can’t ride the high for too long, such is life. But I’m not there yet! To My Pacer

Amanda has paced me at a couple of 100-mile races and never before had I acutely felt the need for a pacer until AC100. Words will probably never be enough to say thank you! Amanda, in the moments when I stalled and broke down, I wouldn’t have made it out had you not pushed me, pushed me to dig deep, pushed me to not give up and pushed me to finish. Thank you for being my friend, for pacing my sorry arse and for not letting me give up when every attempt to take a breath made me want to drop dead. The buckle for AC100 will forever hold your name on it! |

AuthorsOur blog writers are members of Terrain Trail Runners, local athletes just like you, who want to share their love and knowledge of the sport. Archives

March 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed